Slowing Down the Rush to Christmas

A Seven-Week Advent Redux

When I was growing up, there were certain things you just couldn’t buy on Sunday. Entire sections of department stores were simply roped off, and retailers respected the rhythms (and boundaries) of the religious and secular holiday seasons. We didn’t see Christmas displays or hear Christmas music or notice any Christmas ads until after Thanksgiving. And then at some point, the day after Thanksgiving became black Friday, because the woeful accountant’s red ink of year-to-date losses became the joyous accountant’s black ink of profit.

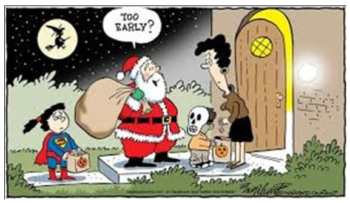

Then some years later, we began to experience all-things-Christmas (and even some all-things-Chanukah) before Thanksgiving; and I remember hearing the adults talk about how this was in really bad taste. And then the unimaginable happened –– the great Christmas extravaganza roll-out began even earlier –– before Halloween. And while most reputable scholars agree that Jesus was not born on December 25 –– a date in mid-late October is likely more accurate –– the driving force behind commercialism is not to explore the historical or Christological Jesus, but to make as much money as possible.

So during seminary, one of my liturgy professors (The Very Rev. William Petersen) pointed out that long ago, the churches lost the religious season of Advent to the secular culture of Christmas; and even when churches observe the four weeks of the Advent season, it’s often observed (in collusion with the culture) solely as a time of preparation for the celebration of Jesus’ birth –– and the great eschatological themes of Advent are eclipsed, and we miss the point that the Christian year “starts with the end of all things.”

He wrote that the great eschatological themes –– best heard, for example, when listening to a choir sing the text of Revelation 11:15 within Handel’s Messiah (“The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Messiah, and he will reign forever and ever.”) are often overshadowed by Christmas-oriented services such as Lessons and Carols –– which are sometimes offered as early as Advent I.

And many churches have also failed to use Advent to challenge the misguided interpretation of fundamentalist eschatology; because if the primary focus of Advent is eschatological rather than incarnational, then a season expanded from its present truncated form of four weeks to a more comprehensive seven weeks that’s in full accordance with the lectionary, seems in order. Many books attempt to do this, but no single book addresses the hearts, minds, and wills of the assembled people of God as effectively as liturgy can. Liturgy is the locus, after all, for the celebration and appropriation of our values as persons being formed and renewed in Christ.

Professor Petersen, and other members of the North American Academy of Liturgy, therefore proposed a seven-week Advent season, and a revised approach to celebrating it (along with resources for worship planners, leaders, and participants) which we’ve used at Two Churches and which would begin to address the spiritual, intellectual, and emotional void that’s created when we rush headlong to Christmas morning.

And neither are North American Protestants forging new ground; not only do Greek and Eastern Orthodox traditions already feature a longer Advent season, but our Revised Common Lectionary presents texts for the late Pentecost season which support this schedule since the readings for Propers 27 and 28, and Christ the King Sunday have also taken a decidedly eschatological turn! And so the practice of a seven-week Advent (which begins this year on November 7) helps us keep our focus less on what will be under the tree on Christmas morning; and more on the timeless values of love of God and neighbor, and the salvation for which Jesus was born in the first place. The world certainly needs this shift in our collective consciousness. God’s peace be with you!